The Black Jacobins is quite a difficult book to read, the bibliography reveals it is based purely on contemporary sources. Letters between state officials in France and San Domingo. While this authenticates the veracity of his writing, it can result in a very challenging read. Every so often one finds themselves snapped out of the book to google the eighteenth century French vocabulary, ‘maréchaussée’, ‘sans-culottes’ etc. While trying to keep up with the story telling prose in which the text is written. Fortunately, this does not take away from what can only be described as the ultimate text on a much overlooked event in history, The Haitian revolution.

What James is able to do so well is rid us of this romantic double sided view history; royalty and masses, owners and slaves. Within the accumulation of events that led to Haitian Revolution were to be many players. The absentee lords in France, the Parisienne Friends of the Negro and radical Jacobins of Parliament. The poor whites, the property owners, the Spanish, the British, the ‘mulattoes’ and of course the blacks. How all of these different forces vying for their own power, ended up in the creation of the first independent Black state is a question that James answers with poignancy.

In ‘Parliament and Property’ he sets the scene for what is to come, documenting the clashes between the poor whites and the highly educated overseers, the mixed race class. The former mostly comprised of bandits and banished criminals, supported the uprising in Bastille, hoping for it to bring a change to their circumstances. The latter wore the red cockade in flattery of the white planters on the island. Subject to violent attacks and lynchings, the creole class were embittered due to their own political status. As they were still prohibited from owning land and voting in the French national assembly. Those that attempted to attain them were hanged.

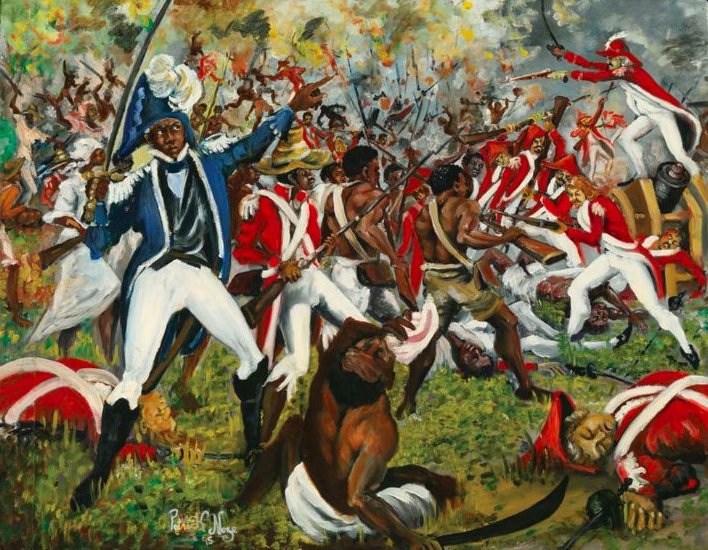

This entanglement was only to be made more complicated by the arrival of the British on the island in 1794. The British were attempting to take advantage of the revolutionary fervour that had swept across the island since the rise of the Creoles. With the intention of reinstalling slavery. But history shows us that great men and women are moulded by the size of their adversity.

Which brings us to the hero of the story, Toussant L’Ouveture. A saint like figure whose intellectual faculties, physical prowess and kindness endeared him to the hearts of all colours of the San Domingo. This was man who in 1793 protected his slave master and her plantation from being set a light by the growing band of revolutionaries. James depicts him as a demigod, driven by emancipation but never succumbing to the racial hatred that had stained the island for over two centuries. A man of exceptional intelligence and remarkable physical ability. He was known to ride his horse for one hundred and twenty five miles a day, and was trained to swim across horrid rivers. He governed his life with extreme discipline and was able to live off two bananas and water for days.

Toussaint’s unique character was shaped by his earlier life, . As a slave he had an agreeable relationship with his planters family. Not only had he never been whipped but as the steward of livestock he made regular contact with other authorities who oversaw the plantations. His vast reading had given him an overview of global politics and military science. All of this was to lay the basis for his political savvy-ness, his letter writing ability. Such as his scheme to allow his white comrade Laveuax to be arrested and taken to France so that he could be elected as representative in the House of 1796.

As the new French constitution had granted seven seats to San Domingo. Toussaint was a calculated political thinker, a combination of unbelievable fore-planning and the shrewdest patience. In 1797 he waited for the most convenient moment before going to the white stronghold hold of Le Cap. Where he gave the French Commissioner and agent Sothonax the ultimatum of being murdered or fleeing to Paris. The reasoning behind which is explained in a long letter to the directory. In which he describes that after his ceremony as French Commander-in-Chief, Sothonox attempted persuasion of Toussaint to murder of all the whites of the island.

Another example of his military genius was his threatening of the British Lieutenant Thomas Maitland, by warning that if British troops did not rescind from Mole St Nicholas in the North and Jérémie in the South. He would send Africans from San Domingo to Jamaica to start an uprising. Afraid of rebellion, Maitland left San Domingo in 1798. Amongst his most formidable achievements were his division of the island into six sections that still remains. Coinciding with his desire to remain amiable to all parties, he created a court system by which there were to be courts in both the French and Spanish parts of the capital.

Furthermore, aware of the Spanish hatred of him and his army, Toussaint extended a hand of peace to Western part of the island. He established a court of appeal to hear their grievances. Repaired many of their roads, and built a two hundred mile long super road from Laxavon to San Domingo encouraging them to cultivate sugar the East. As a way of monitoring the corruption of the merchants he imposed a twenty percent tax on their imports. Agriculture in San Domingo began to flourish ushering in a golden age for the island. He changed the culture within the army by giving favour to officials who were married, and discouraging concubinage. He reconstructed buildings in Le Cap, creating the famous Hotel de la République which became the social epicentre for men of all colours. With his promotion of creole and blacks into positions of power all over the island, racial prejudice and feelings of inferiority began to dissipate.

Where did it all go wrong for Toussaint?

Toussaints grave error was that in his reverence for France he began to isolate the black masses. The latter whose lack of education has left them too ignorant to manage an island the size of San Domingo. Toussaint believed that in order for the island to prosper, he would have to maintain cordial relations with the property owners. It was they who had the knowledge of accounting, finance, duties and so forth. Moreover, he feared reprisals from France and did not want to alienate Paris. He believed that France with its philosophers, Catholicism and its language was the pinnacle of human civilisation. That San Domingo should be an extension of the mother country. In the drafting of the constitution in 1801 no blacks were present. In the document he declares San Domingo independent, but requests French support financially and in local government. Toussaint had already sealed his own fate with his assurances to the property class that they were to remain the owners of their plantations.

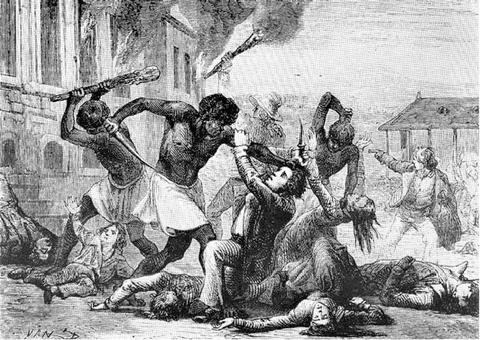

Unhappy with the new deal by which they would have to work for the same white property owners. The Northern region revolted while Toussaint was away at the wedding of Dessalines. They started an uprising in Plaisance and Limbe, killing all whites they were to come across. This revolt was led by Moise, a young revolutionary black who in line with the masses believed labouring for ones previous owners was no replacement of the slave system. Additionally, he sought an alliance between blacks and creoles and didn’t believe in pandering to the whites one bit. Moise had become the face of real revolution and had taken the place of Toussaint, who at this point was out of touch. Further solidifying his non-synchronicity with the blacks was his decision to execute Moise.

In Toussaint L’Ouveture we see the the modern day dilemma of many African leaders, torn between the idealism of their own nations and the pressure to maintain relations with ‘The West’. Would the story have ended differently if he had took a harder line and expulsed or slaughtered all whites. To borrow James expression, he was blinded by “enlightenment.” Or perhaps was his fate sealed with the murder of the people’s hero Moise, the final act that pushed them over the edge? I believe that Toussaint knew that the only way the blacks could be left emancipated was to guarantee to the French assembly that San Domingo would continue to be their source of wealth. It was for this reason that I think he was soft on the property owners. Toussaint would have known of France’s military capability and any threat to the property class would have brought forth the wrath of France a lot more quickly.

Whatever the case, what ensued was to be one of the gruesome battles in history, in which the Africans of Haiti fought to the death for the liberty of their country. The Haitians favoured guérilla warfare over direct combat, cutting French supply lines, munitions and communication. Appearing in French encampments in the middle of the night only to start a blaze then disappear into the forest. Yellow fever and the rainy season played their part in the decimation of an already dispirited French army. Of the 24,000 French army that had arrived in 1801, only a third remained.

History confers the convenience of hindsight. In which we can see that Toussaint’s gravest error was his conviction that Haiti could not survive without France. He sent a letter to Napoleon and the French general on the island Leclerc reassuring his loyalty to the mother country. Toussaint was arrested at a meeting in the headquarters of general Brunet. Deceived by the tone of the invitation that guaranteed his safety, he was seized upon and sent to exile in Paris. Alone in his fetid cell and suffering from the ailments of old age. Toussaint died on April the 7th 1803. Regardless of his flaws, Toussaint L’Ouveture remains one of the most remarkable figures of history. The leader of a revolution that was to catapult the end of the slave trade. The creator of the first independent Black state.