In this magnanimous piece of work Ron Ramdin provides an in-depth overview of the creation of the black working class. From the epoch of the slave trade all the way to our modern era. Texts that set out to cover such a wide-span of history can sometimes suffer from an overload or misapplication of content. One of the biggest challenges to the historian remains, not to merely narrate but to bring the past to life. To awaken the imagination of the reader and immerse them in a world beyond their senses, while still presenting reasonable arguments and factual information. Ramdin achieves this, almost effortlessly, his style is poised, confident and steeped in evidence. All of this he does while providing Marxist interpretations of historical events. Individual motivations for power and wealth are absent here. The relation of capital to class frames the narrative.

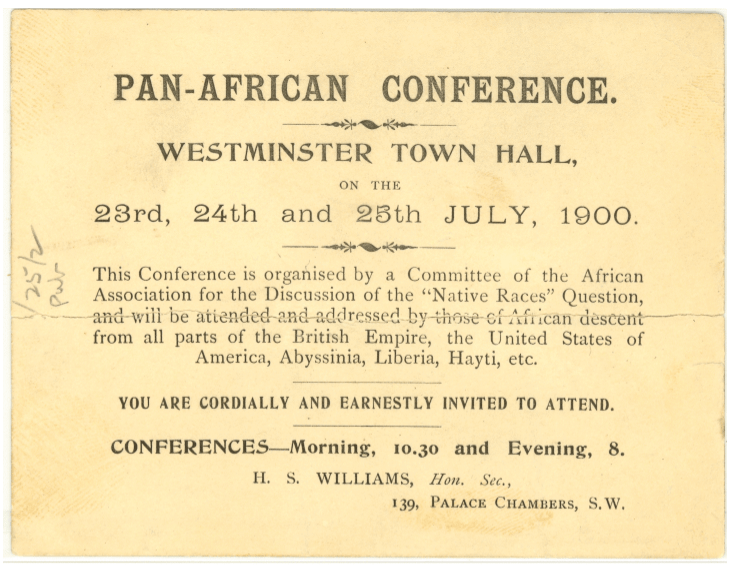

In the third chapter, ‘Post-Emancipation Developments.’ Ramdin sheds light on unknon figures of Pan Africanism; J.A Thorne and Henry Sylvester Williams, the latter, whose plan to settle one hundred West Indian families on the Zambezi laid the foundation for Marcus Garvey’s back to Africa movement. In 1897 his forming of the African Association was to become of crucial importance to the development of Black British activism. The Pan-African conference held by the African Association in 1900, its aim was to speak out against the sprawling British empire and her acquisition of more land on the continent. The address was for European nations to recognize the independence of Ethiopia, Liberia and Haiti. Despite being a gesture of a grand scale that attracted international attention and high profile figures such as W.E.B DuBois. The conference failed in its opening of dialogue with Queen Victoria, as Wiliams’ memorial of concern for the plight of Blacks in South Africa were evaded by Lord Chamberlain.

Ramdin also sheds light on one of the great conundrums of history. The abolishment of the slave trade. The French, and Dutch broke Britain’s eighteenth century monopoly on West Indian sugar. Furthermore, the output of her islands in the Caribbean had declined drastically due to, absentee lordship. . The capture of Guyana and Mauritius was essential she required fresh territories to produce cheaper sugar. The latter increased its production almost three-fold in fifteen years from 55,163 tons in 1850 to 165,000 tons in 1865. The point being, that the replacement of slavery with indentured labour shows that the 1838 abolition was not brought about as a result of some moral epiphany.

Britain is a ‘parasitic economy,’ whose wealth derives overwhelmingly from its empire. This view was echoed in 1929 by Chancellor of the Exchequer Winston Churchill, who went on to further claim that our social services rely on the Commonwealth. Some of the most startling facts to support these assertions; the rise in import surplus from £30 million in 1895-1899 to £134 million to £438 million in 1947. This rise in import debt coincided with an unravelling of the industrial sector. Coal, shipping, agriculture and cotton out put declined rapidly prior to the first world war. Imported goods can spur the income of the secondary tier of an economy but the render the working class futile. It becomes apparent throughout this chapter that these Isles have always been fore-thinkers in economic strategy. In what Ramdin describes as “the exchange of free-trade for mercantile monopoly.”

Following the abolition of the slave trade, Britain began to facilitate the movement of Indian people around the empire. Which included Ceylon, Natal, as well as many islands of the Caribbean. A total of two million people were dispersed around Britain and France’s territories between 1840 and 1870. In the context of history the commencing of indentured labour corresponds exactly with abolition, this coincidence prompts one to ask why would the British seek to replace one form of servitude with another. I believe the solution to this conundrum lies in the understanding two things; 1) Brtish fore-planning – Advanced economic preparation. By which strategists plan for events decades ahead. One notices further that the end of indentured labour occurs at the same time of British foray’s into the African continent. 2) Divide and conquer – The age-old policy used to control and suppress. Indians in the Caribbean provided a buffer-zone between the whites and the increasingly growing and riotous blacks.

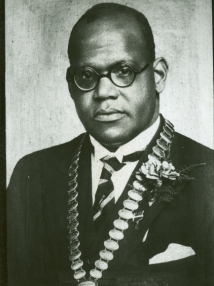

Black British activism in the twentieth century got its kickstart from Harold a Moody, a Jamaican born doctor who started the League of Coloured Peoples. Which was to be an organisation that would dedicate itself to the eradication of the colour bar. As a devout Christian, Moody believed that Whites and Blacks could work together to alleviate the discrimination in which marred the lives of the West Indians in Britain. This led to the name and publication of ‘The Keys.’ Moody contacted shipping companies that disallowed blacks from working, and was able to get them to reverse their decisions. He also contacted authorities from eight cities around the country about the provision of the employment for the disaffected youth of Cardiff. Perhaps a progenitor of the great Dr King, Moody was an incredible galvaniser, but his religious beliefs underpinned his reactionary stance.

In George Padmore was a man who understood the relationship of imperialism to capitalism, therefore he did not become fixated with the challenging its ephemeral manifestations. So while he spoke out against the colour bar in the army and the BBC’s use of the n-word. He wrote several books, ‘How Britain rules Africa’ (1938) ‘Africa and World Peace,’ (1938) and the pamphlet ‘The West Indies today’ (1937). Most importantly, he created the International African Service Bureau, which skilfully took seized events happening around the world and connected them to the condition of the African. At the Pan African Federation of 1944, Padmore continued to guide and create an ideology for the removal of colonial governments on the continent. These series of Congresses gave birth to a development of consciousness. At the fifth assembly, it was decided that there was to be a West African Federation and another meeting for the planning of United States of Africa. Without romanticism Ramdin provides an in-depth analysis of the Black British activism and how it has been developed largely by immigrants from former colonies.

The murder of Kelso Cochrane in May 1959, had been preceded by a year of tumultuous violent attacks against blacks in the Western stretch from Kensal Rise. ‘Nigger-hunting’ tours were carried out by far-right groups like the Union Movement. These acts of aggression included attacking black people walking by themselves, fire and petrol bombing of houses. The setting on fire of a house in Notting Dale triggered a fight involving hundreds of whites against the West Indians. While his death hastened the National Labour Party, the White Defence League and the Union Movement into the spread of more propaganda. It also galvanised the West Indian community and gave birth to the Harmonist Movement. Founded by MacDonald Stanley, the Harmonist Movement was intended to bring about racial harmony between blacks and whites. Which opened in November 1958 and spread to other parts of London. It also urged the West London Caribbean committee into the need for newspaper that relates to their experience and addresses their problems. This need was met by Trinidadian journalist Claudia Jones. Who started the West Indian Gazette. Which also organised the first Carnival.

In the next chapter, Ramdin presents the core of his thesis, the discriminatory policies that blacks in Britain were to receive, need to be seen in the context of the international exploitation of labour. The labour gap caused by the advancement of white working classes into more service industries created a demand for a new working class. Their political status as migrants makes their potential for financial exploitation much greater. We often take discrimination at face-value, a product of the visceral and savage behaviour of hooligans and thugs. In our horror of teddy boy attacks and petrol bombs, we lose sight of racism as an economic function of capitalism. This is what Ramdin is able to elucidate so well, racism became the justification for exploitation of first Africans and then Indians. In the US there was the three-fifths of a human rule enshrined in the constitution. Similarly colonial law categorized all Black Africans the property of their masters governed the British ruled islands. Laws are put into operation by the capitalist class to maximize financial gain. We see an intensifying of this in the twentieth century as in the next chapter Ramdin documents the industrial labour protests of Asians. The first is at Courtalds Red Scar Mill in Preston, which started over the managements forcing of workers to function more machines for less pay. The arrangement of a deal between the management at Red Scar and the Transport and General Workers Union resulted in a 50 per cent increase in output for 3 per cent increase in wage. The workers, most of whom were Indian and Pakistani went on strike for three days. Although Michael X of RAAS (Racial Adjustment Action Society) remained outspoken. His organization was not equipped to deal with an industrial workers movement to challenge corporations. Nevertheless, it highlighted the lack of union support.

Followed by the Imperial Typewriters strike in Leicester, on May Day in 1972 more than 500 East African Asians workers walked out of the factory, aggrieved by managements overlooking of their concerns. Primarily because of bonus rates and the expectancy to do more machines with the same pay. There was also the concern of favourable treatment of white workers. It was in this strike in which the Asian women began to shatter the passive wife image that was held by so many. On the picket line, they produced a loud thrashing sound every time a member of management walked out. The Asians carried the strike forward dynamically, gathering funding from various community organizations and setting up an inquiry into the two lieutenants of capital. Tom Bradley, President of the Transport Salaried Staff Association and Reg Weaver the TGWU convenor. Both of who had attempted to dissuade the picketers. Although most of the strikers were sacked, this was an event that exposed the TGWU and the larger paradox of using the instruments of a system to defeat it. Nowhere was this struggle more apparent than at the Grunwick strike of 1976.

The North-West London printing firm had 429 East Asian Africans on their workforce, most of whom were women. One of them a young Devshi Bhudia, who along with three other workers decided to work slowly as a protest to; the thirteen crates that he was required to go through and compulsory overtime. This momentum was picked up by one of the workers, Jayaben Desani who became the leader and galvanizer of this fifteen-month strike which had amassed 20,000 people by July 1977. These Asian women in sari’s stood outside the company building on Chapter Road with pickets demanding better conditions. Grunwick was in many ways to become a foreteller of the frustrations that Blacks would encounter when challenging the illegal practices of institutions. The failure of APEX, the and the general TUC to bring about any effective change to working conditions. Although of good intentions, the head of the TUC Jack Dromney was detached from the daily problems of the Grunwick workers. He placed too much faith in his belief of trade unions as a force of good. As previously mentioned, the problem of using the machinery of the state to combat the state.

In ‘Organisers and Organizations’ Ramdin credits Stokely Carmichael with introducing ‘Black Power’ to Btitain. He spoke at the Dialectics of Liberation in London 1967 in which he interlinked the struggle of blacks in Britain to the wider battle of the third world against the capitalist class. In order for black power to be achieved all blacks would have to unite across territorial and language barriers. The old methods of fighting had to be abandoned and blacks should through the taking of power of their community control their own destiny. Carmichael also spoke at rallies in Brixton, Notting Hill and appeared on the BBC. In 1966 the dissolution of CARD (Campaign Against Racial Discrimination) was brought about by a schism between the dissidents and the majority. Led by Grenadian born House of Lords member and medical doctor David Pitt who believed in the integration of whites into the group. Whereas the dissidents maintained that the group should be under the full control of immigrants.

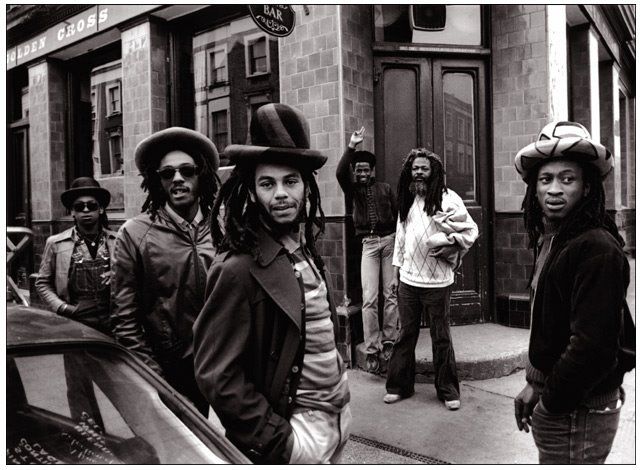

Every underclass develops its own social norms as a response to rejection from the dominant society, with black people in the seventies. This manifested through two beliefs; Rastafarianism and the Yoruba origin, the Church of the Cherubim and Seraphim. The latter which had arisen out of Jamaica in the 1930’s but had taken forty years to find its medium through reggae music. With its message of African pride and its rejection of European customs, Rastafari became an inspiration for a generation of disenchanted black youth. In the final chapter of the book Ramdin attribute the development of Black Woking Class Consciousness to the militarization of the black community between the late 1970’s and 1980’s. With the introduction of riot shields, ‘sus laws,’ Special Patrol Groups, who were deployed in parts of London with high concentrations of black people. All of this was a response to the high unemployment, which remained throughout the latter decade, the riots of Afro-Caribbean communities in Brixton and Tottenham. Must be perceived as the culmination of a class-consciousness and a rebelling against the tiers above.

The Making of the Black Working Class in Britain is an incredible read, it is heavily detailed and the writer expresses his arguments with a riveting poignancy. Ramdin unearths so much of the Afro-Caribbean struggle whilst providing his own Marxist interpretation of events. It is a book hat deserves much wider excavation by historians interested in the struggles of black and brown Britain.